YOU CAN'T FART WITH IMPUNITY while a ceiling fan spins overhead. It’s the same concept as getting caught in the jetwash. If you pushed the power on your engines up too high when taxiing around on the ground, the wind and fumes from your tailpipes, the jetwash, could knock over a crew chief standing in your blast cone. Two summers earlier, in the big hit Top Gun, when Maverick flew into Ice Man’s jetwash, he slipped into a flat spin and went out to sea. Maverick and Goose had to punch out. And Goose died, because he smashed his head on the canopy. But I wasn’t thinking about that. All I could think about was that my insides were growling almost as loudly as the bedroom ceiling fan above me was rattling.

We started flight school the summer after Top Gun. At the beginning of our training—now ten months past—our aerospace physiology lessons stressed the importance of equalizing pressures inside the body during climbs and descents to keep up with changes in atmospheric pressure outside the body. Anticipate the changes. Stay ahead of them.

I definitely had pressure built up inside my stomach as I descended from the alcohol-induced high of the previous night. My stomach was gurgling and rumbling out of control. I couldn’t keep up with the changing pressures. For ear pressure, you yawned and stretched the Eustachian tube in your inner ear to deal with trapped gases inside your head. Upon descent from altitude, as the pressures around your body increased, you performed the Valsalva maneuver by plugging your nose and attempting to blow through blocked nostrils until your ears popped.

For gastrointestinal pressure, which hit during the climb to altitude, student pilots learned the Air Force’s unofficial pressure equalization technique: the One Cheek Sneak. Without drawing attention to yourself, dig one cheek into your seat, lean, and lift the other cheek ever so slightly to spread the two out wide. Release the gas slowly with control, and most importantly, pretend like you’re not doing anything. Polite, discreet, necessary, and very effective.

I knew I’d never get back to sleep if I didn’t equalize the pressure in my stomach with the bedroom atmospheric pressure. The only thing that concerned me was being so loud my roommates heard. Slowly and silently, I initiated the diffusive process with a flawless execution of the One Cheek Sneak.

Much better.

Relief was instant, but almost as instantly, my jetwash blew back into my face, courtesy of the ceiling fan. Wind, hot fumes, and a flat spin, the consequences were inescapable.

Instead of jet exhaust, however, these fumes reeked of tequila. I had forgotten I drank tequila, which explained why my mouth and throat were so dry. It also explained my buzzing headache.

As I lay on my bed, having closed my eyes again, the room spun faster than the ceiling fan. I didn’t know which one spun left and which one spun right, but I did know I was about to get sick. And for the first time since I woke up, I noticed there was no cool air. It was hot. Wicked hot. The air conditioner had broken again. I was starting to think I had to punch out of bed.

Nothing worked right in our house from the time we first moved in. Kenny and I had been renting it for just about the full year of flight school, which started two months after graduating from the Academy. Doley only lived with us since February. Month in and month out, something needed to be fixed. This month, it was the air conditioning, and this was maybe the third time the AC had broken down—not a good thing in Mississippi in the middle of June, when every day is ninety degrees or hotter.

Yesterday, I bet it was a hundred!

Even after the sun went down, it stayed hot. I’d never lived anywhere hotter. Growing up in Rhode Island, we probably had three days each summer over ninety degrees. At the Academy in Colorado, where I studied as a cadet, you might get to ninety degrees for about a week in the summer, but after the sun went down behind the mountains, the nights were always cool. Sometimes even cold. But in Columbus, Mississippi, I regularly saw temperatures over a hundred on the local Chevy dealer’s time, temp, and message sign. Once, I even saw a hundred and twelve!

Above my bed, the ceiling fan wasn’t aligned correctly. As the fan blades spun and the light fixture hula’ed around its y-axis, the beaded metal pull-chain circled and scraped the glass fixture upon each revolution with a tiny clink. Every fourth rotation, the wooden knob at the bottom of the pull-chain rotated fast enough to swing up and knock the lamp, making a much louder clink!

The beat reminded me of a marching cadence back at the Academy.

Clink. Clink. Clink. clink!

HuP. TooP. ThreeP. FourP!

When you called out a marching cadence, you were supposed to add the “P” sound to your numbers to emphasize the point in each step when marchers’ heels were supposed to dig into the ground. Supposedly, the extra “P” sound made the calls extra sharP and crisP.

As much as I appreciated a good marching call, this clink was wicked annoying. And as a second lieutenant, I wasn’t a cadet anymore. Without AC, though, what other choice did I have besides the fan?

Maybe outside?

I didn’t know.

I sorted through chaotic images of this insane party the night before. The white poster board taped to the side of the beer truck announced forty-seven kegs downed so far—though that might have covered Friday night, too. The drummer from the band had the tequila—that, I remembered. He came through the dancing crowd with two bottles and poured shots into people’s mouths. The band called it their crazy set. They’d come back from their second break wearing cat makeup, which was weird. But they were loud, and the party was good. They were just having fun.

I remembered Lieutenant Holtzmann, a T-37 instructor pilot, tumbling down the long, wooden flight of stairs from the upper deck of the restaurant’s porch all the way to the sand at the bottom. Proffitt’s Porch restaurant sat at the edge of the beach near Officers’ Lake. You’d get your food inside from Mr. Proffitt or some member of his family and take it out on the porch overlooking the lake. Lieutenants Holtzmann and Hartlaub, another T-37 instructor, sang and acted out the lyrics to “Swing Low, Sweet Chariot” at the top of the stairs during one of the band’s breaks. It appeared to be some kind of tradition of theirs, because they had coordinated all their moves. A lot of people watched. Their fellow instructors sang along. After they finished, I don’t know if Lieutenant Holtzmann fell or if he was pushed, but his long fall down the steps was funnier than their routine.

At the bottom of the stairs, he staggered and stumbled and almost fell again, getting to his feet. I couldn’t tell if he was hurt or just drunk. Then, Lieutenant Holtzmann dropped to his hands and knees in the sand and began to crawl. I quickly made my way over to check on him—as if I were in any condition to help.

As I pushed through the crowd, he started looking for something, presumably something he’d lost in the sand as he tumbled down the long flight of wooden steps.

Yup, just confused!

I figured he’d lost his teeth.

Lieutenant Holtzmann normally wore a bridge of false teeth, fitted like retainers teenagers wear after they’ve had their braces removed. He’d lost his real teeth in a car wreck years earlier. As he stumbled and crawled around, mumbling to himself in a familiar Rhode Island dialect that sounded like baby talk while nobody else paid any attention, I laughed.

He was okay. And because I was a student, and he was an instructor, I didn’t offer help.

In Undergraduate Pilot Training, students pilots and instructors pilots didn’t mix. Though officially equal as Air Force officers, that didn’t matter. Lieutenant Holtzmann and I might both be Rhode Islanders, with even some of the same friends in high school—but students and instructors didn’t mix. So I left him sifting in the sand on his hands and knees. Babbling his Rho Diland baby talk. He’d find his own teeth…eventually.

I sneaked back into the woods to urinate because I figured the trees didn’t stink as badly as the port-o-potties, and the line looked a lot shorter. Instead of a private place to pee, however, I discovered a few guys from a class behind mine, the idiots known as the Nightmares, in a small clearing.

The Nightmares spent too much time in flight school trying to garner favor from the leaders of Columbus Air Force Base with their stupid spirit missions. But their pranks always turned out to be jokes at the expense of other classes. So, most classes on the base couldn’t stand the Nightmares.

They’d stretched the biggest slingshot I’d ever seen between two trees about fifteen feet apart. The ringleader was all business, inspecting their stockpile of water balloons for proper size and knotting techniques, planning his targets, calling out adjustments to launch angles to correct for wind, and giving the orders to fire.

His classmates were using the slingshot to launch water balloons up to the edge of the stratosphere so that they’d descend on their targets from above without giving away the position of the launch site. After launching about a dozen projectiles in different directions, the Nightmares unhooked the tubing from the trees, cleaned up any evidence that might have pointed to their having been there, and moved to a new position to establish another discreet launch location.

I concluded a quiet pee.

Jerks.

I remembered I ate dessert inside the restaurant with Doley very late into the night. Mr. Proffitt’s chocolate chess pie. I had to eat.

I remembered I puked. At least once. I had to puke. That happened before the dessert.

I remembered I drove Kenny and Doley home.

Very stupid!

I shouldn’t have done that.

My head really hurt.

I was thirsty.

I knew that I wouldn’t get back to sleep in my room. It was way too hot. The clinking grew louder. The spinning spun faster. I thought maybe in the backyard I could lie in Kenny’s hammock and sleep in the shade. Maybe, there would be a cool breeze. Maybe, it would be quiet. Maybe, the images from the party would stop racing through my head.

So I got up and sloshed barefooted across the swampy shag carpet to the bathroom. The water from the AC unit that had pooled up in the rug oozed between my toes as I stepped across the hall. When I stepped onto the bathroom linoleum with my wet feet, I just about slipped and fell.

I used the toilet and washed my hands. I tried to drink cold water from the faucet to help myself feel less sick. It didn’t work. When I bent down and stuck my head under the tap, I got dizzy, lost my balance, and almost fell again.

I could have used a good teeth-brushing, but I hadn’t picked up a new toothbrush since I’d visited the Dental Hobby Shop last August. The bristles on my old brush had gotten so mashed down and hard that brushing my teeth with a Lego would have been softer. So, I just squeezed some toothpaste onto my finger and rubbed and swished and spit. It helped.

I’d slept in my bathing suit and my favorite pink flamingo tank top that I’d worn to the party. Filthy, I stunk of sweat, bug spray, and sunscreen. I never did go swimming in Officers’ Lake, because as hot as it was, the cloudy, dark, and stagnant lake water was just disgusting.

Imagine swimming in hot chocolate—the kind made with water, not milk. Instead of sand beneath your feet, imagine warm muck. Throw in floating tree branches and aggressive water moccasins. That’s Officers’ Lake! I didn’t find this refreshing, but it didn’t stop people from swimming or throwing others into the lake.

I waded back through the shagmire in the hallway, past the air conditioner that spit on my ankles, as if to spite me. The pooling water stunk. Already thirsty again just five steps from the bathroom, I checked the fridge for something else to drink on my way outside. But inside our orange 1950s refrigerator, we had nothing but the condiments we bought when we first moved in—a bottle of runny ketchup and a jar of watery mustard.

I should have worn my flip-flops outside. We didn’t have a lot of grass in the backyard—not like our next-door neighbors, Diane and Dennis. An older, retired couple with no children that we knew of, they worked on their beautifully landscaped and manicured piece of property lawn all the time. Our yard was an eyesore. We had dirt, lots of roots, and spiky pine cone-like balls that had dropped from the trees. We never raked. We never watered. We almost never mowed. We had fire ants. Lots of fire ants.

My feet weren’t very tough, so I tried to pick my spots and step on grass only, as I made my way to the hammock. Next door, Diane and Dennis had already changed out of their church clothes and were diligently working on their lawn and shrubs, as they did every Sunday. I waved and smiled a hello.

They were nice people—older than my parents. They had a nice lawn. Nice grass, nice bushes, nice trees, and a nice house. Always nicely dressed. We probably gave them nightmares with our unkempt yard and late-night parties. I’m sure they prayed for us.

As I climbed into the hammock and stretched out my wet, dirt-covered feet and toes, I realized it was way hotter outside than inside. But it was too late. I’d already committed to the hammock; there was no going back. I’d made my bad decision, and I was going to stick with it. Like an idiot.

The sun was too bright. The air was too thick. My mouth was too dry. My headache was too strong. The images in my mind were too loud. There would be no sleep. There was no going back. So I fidgeted uncomfortably, closed my eyes, and tried to catch up with the racing images of the party from the night before.

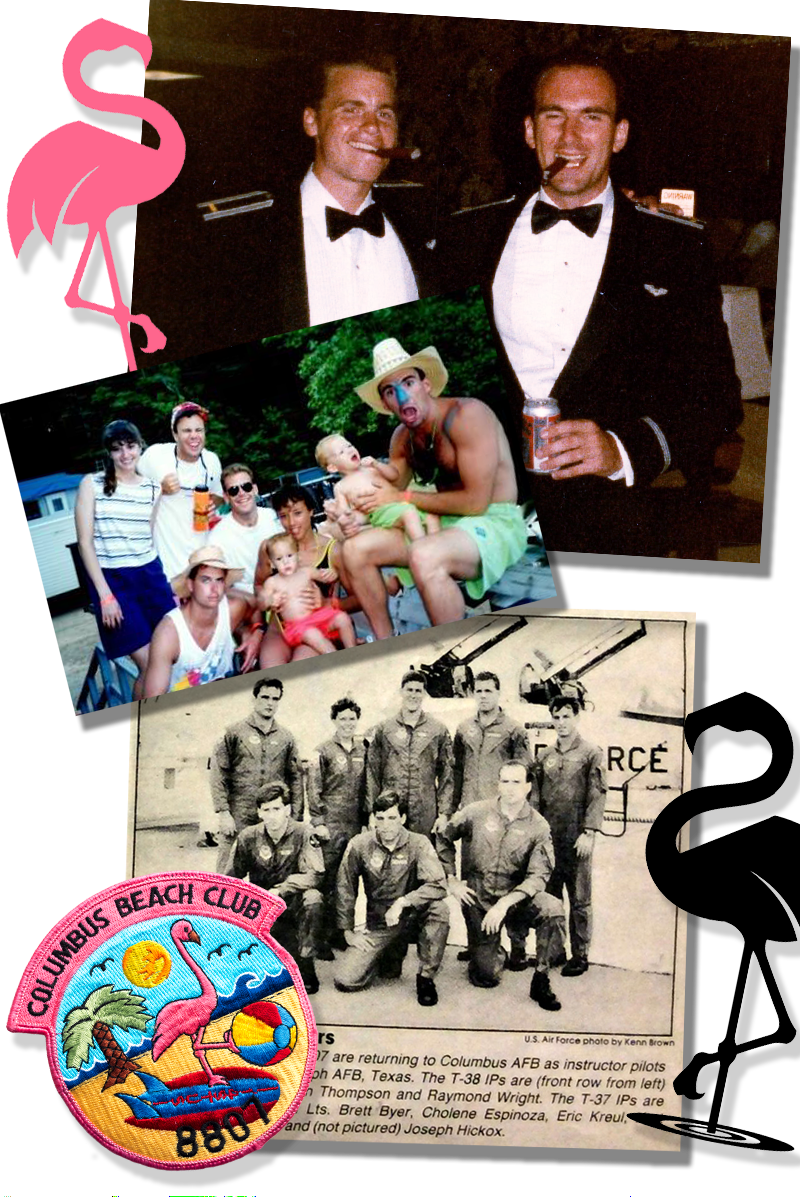

Ten months spent in Columbus, Mississippi. Seven weeks from graduation. Six days until Assignment Night. So close to getting my first Air Force assignment and so close to becoming a real pilot…yet I still didn’t feel comfortable partying with instructors. We were supposed to keep our distance. But at the FAIP Mafia Party, rules didn’t apply.

The FAIP Mafia was the unofficial name of an anonymous and, officially, non-existent fraternity of young instructor pilots who kept the training squadrons running in spite of the questionable leadership and management skills of the senior officers assigned with such tasks at the base. The Lost Weekend, a trilogy of back-to-back-to-back parties: Friday, Saturday, and Sunday, served to help the entire base blow off the intensifying pressure as our year of flight school drew to a close.

According to the tradition, the Friday night component of the party was held at the Officer’s Club. I didn’t hang out at the O-Club much, so I didn’t go. My guess was that Friday’s party was a diversionary tactic so that when senior officers on base heard talk about a party, they’d assume that it was the Friday night gathering at the O-Club, where many senior officers went on Friday nights. The second and third days of the party moved off base to the remotely located Officers’ Lake, a little swimming hole with a sandy beachfront and a great family-owned restaurant called Proffitt’s Porch at the backside of the lake’s beach area. You could only get there by dirt roads or by parachute.

Lying in the hammock with my eyes closed, my mind still racing, and the world still spinning, I heard the back door open, and I looked over to see whom I’d woken. It was Kenny. Dressed only in tighty-whitey underwear, a sleeveless white undershirt, and his dark-lensed eyeglasses with a wrap-around strap, Kenny twirled his lacrosse stick as he stepped out onto the back patio. He had been the goalie on the Air Force lacrosse team. As the kitchen door closed, Kenny stopped, gave an imaginary opponent a couple fakes, and threw his lacrosse ball off the brick wall on the kitchen side of the patio. As it bounced back, he scooped it with the net of his stick. Then, he threw a couple more fakes at his opponent.

Satisfied that he’d juked a defender, Kenny grabbed a lawn chair from the patio and dragged it behind him in his right hand as he continued to shake his lacrosse stick back and forth in his left. Clearly, his bare feet were no tougher than mine, because he hobbled across the spiky pine cone balls and roots in the yard.

The closer Kenny got, the harder I had to fight to keep from laughing. I might have been in bad shape, but Kenny looked like a cartoon character that just had a stick of dynamite explode in his hand. His face was dirty, he had no clothes, and his normally gelled and spiked hair blasted out in every direction. I spotted a huge black and purple bruise on his leg, like one you might get from playing tackle football without pads. And then, there was the wax on his neck and shoulders. Oh yeah, I remembered that.

Kenny didn’t stop until he got a little too deep into my comfort zone for a guy lying in a hammock talking to another guy in a pair of tighty-whiteys.

“Aaay! What happened?” he asked.

“You drank wax.”

“What?” he asked, like he had no recollection of drinking wax.

“You drank wax. All around the party, there were little metal buckets that burned orange candles that supposedly keep mosquitoes away. As the candles burned, the wax turned to liquid, and you’d pick up the bucket, and drink it. Then you’d cough up a wax ball from your throat back into your hand, and once the cud cooled, you’d throw it at somebody. Usually me, you bastid,” I said.

“No wonder why my throat tastes like shit,” Kenny coughed. “Aaay! That stuff almost tastes like tequila.”

“You drank that, too.”

“Who had the tequila?” Kenny asked.

“The drummer,” I said. “He walked around the crowd and poured tequila down people’s throats. He had a bottle in each hand. That was during the band’s crazy set.”

“Aaay, that whole party was crazy,” Kenny said. He pulled his lawn chair around to the tree at the end of the hammock where my feet were. Thank goodness. But then he put his right foot, which was his outside foot, up against the tree. Not a good pose for a guy in his underwear. Still holding his lacrosse stick in his left hand, Kenny rubbed around the giant black and purple bruise on the inside of his thigh.

“What happened to your leg?”

“Fuckin’ water balloon!” he said incredulously.

“What?” I pretended I had no idea how a water balloon could travel fast enough to leave such a mark.

“Aaay, I was takin’ a piss near the woods. I hear a snap! like someone shot a giant elastic band, and then it feels like I get hit in the leg with a lacrosse ball. The water balloon was like an ice ball. I think it had ice in it, and it was goin’ a hundrit miles an hour. It hurt like a bastid!” Kenny cried out.

“Good thing it didn’t hit you in the eye. You know, it’s all fun and games until someone loses their PQ.” I quoted a universal Air Force Academy truth about the importance of being PQ: Pilot Qualified.

“Good thing it didn’t hit me in the eye?!” Kenny screamed. “Good thing it didn’t hit me in the fuckin’ balls!” And with that, he opened up his legs even wider, dropped his lacrosse stick, and pointed at his balls with both hands.

“Dude! I don’t need to see that.” I closed my eyes and looked away.

Kenny’s operating envelope, to use pilot terms to describe the parameters of one’s behavioral comfort levels, had taken a lot of getting use to over the past year. If the graph plotted Things You Comfortably Say on one axis and Things You Comfortably Do on the other, our values for the things we’d comfortably say would be close. But I wouldn’t even measure up on the same scale as Kenny for things that I’d comfortably do.

Like me, Kenny was out of place in Mississippi. I was Rhode Island, and he was Long Island, and neither of us assimilated into the ways of the South over the past year. But this would be over soon. We were less than two months from UPT graduation and our first flying jobs in the Real Air Force…unless, of course, our first assignment was to be FAIPs—First Assignment Instructor Pilots. We’d find out at our class’s Assignment Night. Friday night. Less than a week away.

The back door from the kitchen opened again, and both of us turned to see Doley, another misplaced Northerner—Massachusetts—coming out to join us. While Kenny and I were clearly suffering physical pain and looking like we’d just walked away from a Class A Mishap, Doley was showered and clean shaven. His Top Gun flat top was perfectly coiffed, as usual, and dressed in khaki shorts and an Izod shirt, he looked as if he might be headed to church.

“What a great pahty!” Doley proclaimed in a thick Boston accent and smiled.

“Doley, I can barely open my eyes; I’m so hungover. How are you even standing right now?” I asked. “You were worse off than I was last night.”

“Ray, I’ve always said, A little vitamin B and two glasses of water before bed…and no hangover in the morning. I feel great.” Doley smiled again and jogged back to the patio to grab a lawn chair.

“Bastid,” Kenny shot back at him and gave him a couple of fakes with his lacrosse stick.

Doley carried his chair back over to the side of the hammock and took a seat with Kenny and me. “There is one thing I can’t figure out, though,” Doley began. “I don’t know if this was real or if it was paht of a nightmare I had last night.”

“What?” I asked.

“Well, this is gonna sound nuts, but I have this image in my mind of Lieutenant Hahtlaub starin’ me in the face with his mouth wide open, and he had three rows of teeth…like a shahk!” Doley made a shark face for us. “It was the freakiest thing.”

“What?!” Kenny shook his head, laughing in disbelief.

“That was real,” I told them, having seen the other images of Lieutenant Holtzmann flash through my head earlier in the morning. “Hartlaub was wearing Holtzmann’s teeth!”

“What?!” Kenny shook and laughed in disbelief again.

“After the band finished their first set,” I explained, “Hartlaub and Holtzmann sang ‘Swing Low, Sweet Chariot’ with a bunch of crude gestures. Right after they finished, Holtzmann took an Aunt Bunny fall down the steps of the deck. I found him on his hands and knees, combing through the sand, because he couldn’t find his bridge of false teeth. I bet Hartlaub tried to yank them out of Holtzmann’s mouth at the top of the steps after their song, and in their fight over the teeth, Hartlaub won and pushed Holtzmann down the steps. Hartlaub must have worn the teeth around the party for the rest of the night while Holtzmann gummed his beer.” At least, that’s how I figured events had taken place.

“I didn’t see Lieutenant Hartlaub with the teeth,” I finished telling them, “but I saw the rest of it. That’s how I know it was real.”

“That’s just bizzah.” Doley smiled. “So, how’d we get home?”

Kenny just looked over at me and shook his head.

“I drove,” I confessed.

“You dumb bastid,” Doley shot back.

“I know. That was stupid,” I agreed. “You guys remember? I made Kenny hook up the radar detector before we started back, so we’d know if a cop was around.”

“So, what…?” Doley began to laugh now, too. “So, if the radah detecta went off, you’d know to drive more soba? Or were you gonna use the faw wheel drive abilities of the Isuzu P’Up—”

“Winner of the Baja 1,000,” I interjected.

“Winnah of the Baja 1,000,” Doley conceded with a head nod and hand roll. “Were you gonna go off-road and evade the cops because they wouldn’t be able to see you, the only cah around for miles, crunching through the bramble with your headlights on the whole time?”

While keeping two hands on an imaginary steering wheel, Doley got up from his lawn chair and started in on me.

“Beep-beep. Beep-beep. Radah detecta! It’s the cops!” Doley slurred loudly. Then, he hit me one more time with: “You dumb bastid.”

“Yeah,” I agreed. “That was stupid.”

I could have killed someone. I could have killed all three of us. It’s all fun and games until somebody loses his PQ. Or his top row of teeth. Or takes a life.

Seven weeks from graduation. Six days from Assignment Night. About to find out the first flying assignments of our Air Force careers. What cool jets would we get to fly? What exciting roles would we play in fighting the Cold War? In defending our country? In supporting freedom and liberty around the world? What fun and exotic locations would we be stationed at? What country? What city? What mountain? What beach?

“You know what really sucks about that pahty last night?” Doley asked, making sure he had looked both Kenny and me in the face before providing the answer. “In three years, we’ll be runnin’ it.”

FAIPs.

Nobody said a word.

We sat there and thought about this possibility.

Upon completing flight school, some student pilots would be selected to remain at their training base to become instructors for the next classes of student pilots. No one ever told us this at the Academy.

As cadets, we all thought that when you finished UPT, Undergraduate Pilot Training, you moved on to an F-15, F-16, or a bomber, tanker, or cargo plane, a life of travel and big adventure in the Real Air Force on your way to becoming an astronaut or a test pilot.

Or so I thought.

What you learned soon after arriving at Columbus, however, was that a lot of us would probably have to wait for a life of travel and big adventure. In an average year, 20–25 percent of graduating student pilots were chosen to be instructors and remain at the base where they trained, except for the special training base in Texas, where everyone who graduated would be assigned to fly fighters.

No next great adventure beyond Columbus, Mississippi.

No flying jets around the world.

No fighting communists.

Assignment Night was Friday. We had no idea what fate and the Air Force Personnel Center might have in store for us. What aircraft? What mission? What continent? What base?

Mountain or beach?

Or would we even get out of Columbus? Were we doomed to repeat UPT over and over again, class after class, because we’d come back as instructors?

I closed my eyes and sucked in a deep breath of hot, wet Mississippi air. I was worrying too much about my next assignment. I needed to focus on getting ready for my upcoming checkride. If I couldn’t pass it, I might not even graduate.